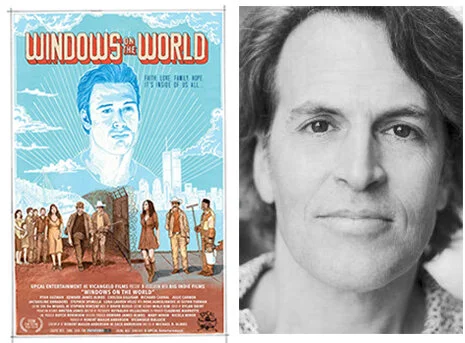

Open Windows: David E. Russo contributes to a very different kind of 9/11 film.

by Chris Hadley for Film Score Monthly

The new film Windows on the World, directed by Michael D. Olmos, pays tribute to the undocumented victims of the September 11th terror attacks and honors the courage and sacrifices of America’s immigrant community. Ryan Guzman co-stars as Fernando, the son of an undocumented immigrant by the name of Balthazar (played by Edward James Olmos, father of Michael D.), who trekked from his native Mexico to work as a busboy at the World Trade Center’s upper-floor restaurant, Windows on the World. On duty when the World Trade Center was attacked on 9/11, Balthazar may or may not have survived the destruction. Yet when Fernando journeys to New York to search for his father, the outcome is as bittersweet as it is bewildering.

David E. Russo, who also wrote the music for several original songs on the soundtrack (now on Ropeadope Records), conceived an underscore that ties itself to New York’s diverse musical heritage and the emotional connection shared by the film’s primary characters.

Chris Hadley: How and when did you become involved with Windows on the World, and what attracted you to it?

David E. Russo: Robert Anderson, the producer and co-writer, is a really good friend of mine. I’ve known him since the ’90s and he’s a fascinating man—his personal story and his creativity. I’ve scored one film for him in the past [the 2008 horror movie Pig Hunt], and so it really was born out of our friendship that he invited me to work on the film.

CH: This project was in development for years, and it apparently went through many changes before Robert finally decided to make it himself.

DER: Right. I forget the particulars of it, but I know it was optioned by Miramax. It’s amazing that films ever get made. But yes, it was an odyssey to get it made, but it was something that he felt really strongly about. He’s a ninth-generation Californian and he’s Mexican on his mom’s side. I know what he was saying when he was reading the article about all the people at the Twin Towers who worked there who were undocumented, who just vanished and whose families didn’t get any kind of compensation. It was a story that he wanted to tell.

CH: He did a great job of telling that story through Ryan and Edward’s performances.

DER: Great cast. The idea of a film with a Hispanic cast, director and star—where it’s not about drug dealers or gang bangers—is a very rare animal. So, that’s something he really wanted to do.

CH: What impact did those performances and the story itself have on you when you were working on the score?

DER: I’ve grown up here in Los Angeles, so I think our population is predominantly Hispanic, but it just made me more aware of how blessed I am. I don’t know if that’s the word, but how I’m part of the dominant culture and have enjoyed what that brings—what is laid at my feet that I don’t even have to work for. So, it’s always been in front of my face, it just makes it more salient.

CH: How difficult was it for you to stick with this project given the problems Robert had in getting the film out there the way he envisioned it?

DER: It wasn’t a problem because it was a labor of love, so this was not a movie that I did for money. It was a movie that I did for the love of my friend Robert, and for a story that he was trying to tell. It took us a while to get it done, but it didn’t really matter. I was doing it at the same time I was doing Gotham, and it went into Pennyworth, but [Robert] would come down here for a few days and stay, and we’d work on music. So, I lived to make music and to be able to do it with a friend I respect and admire. It doesn’t matter how long it takes, and I’m just glad that it was him. He was able to finally realize what he was trying to achieve and say.

CH: What has working with him taught you about being a composer and about collaboration?

DER: I think one reason that we’re such great friends is that he is fearless and courageous, and that is instructive. If you look at his life, it’s about taking chances and going for it all the time, but with a lot of humanity and a lot of love. So, it’s a reminder to be fearless, to go forward and be willing to fail and willing to humiliate yourself—it doesn’t matter. It’s the value of being able to lead a creative life—being able to express yourself—it’s worth whatever discomfort comes with it, so it’s a gift.

CH: That’s pretty much how you approach your creative life?

DER: Yeah. I’m just so grateful that I get to make music every day, and I would do just about anything to be able to continue that. I’ve been blessed for a long time to even have a career. There was nothing in my personal past that would indicate that I should have had any kind of career, so I just feel so lucky to be able to do this. It’s that imposter syndrome—I keep waiting for someone to say, “Wait, wait, what is this guy doing here? Get this guy out. What’s he doing here?”

CH: In a recent interview, Robert said that he wanted the music to be “a sonic landscape for New York, suggesting the different neighborhoods there.” How were you able to achieve that, considering that all kinds of diverse genres and styles co- exist in New York City neighborhoods?

DER: When we got into it, the first thing I did was write a suite of music based on the script. For me, the emotional center of the film is the family, their story and the story of this young man’s odyssey. Those had nothing to do with New York, so the music I wrote initially was about that family and stuff that felt true for them. As we got into it, we needed the contrast of the melting pot of New York.

Robert was on the board at SFJAZZ [an educational institution/performance venue for jazz music in San Francisco, California], and he was one of the guys that spearheaded raising the $69 million to build it. He’s an incredible jazz enthusiast, so when we got to the stuff in New York, he called his friends: David Sanchez, Eric Harland and Edward Simon, incredible composers and musicians in their own right. Because there was no money for the film, they provided music for New York, so it wasn’t something I had to create. We ended up doing some source songs, but the great New York stuff was done by these other New York jazz musicians. I would love to take credit for it, but I can’t!

CH: On the subject of settings, specifically Mexico and New York City, how did they inspire the thematic and instrumental elements in your score?

DER: There’s an amazing artist, Sandow Birk, who drew the little interstitial drawings [in the film, representing the journey of Don Quixote]. The young man is reading Don Quixote, and he sees the idea that he’s on this journey. It’s a bit mythic, and those drawings in particular inspired the spirit of what the score should be embodying. There’s a little bit of an out-of-time quality to it and a bit of mythic family magic that I was trying to weave into it. That was the main inspiration, and those drawings were really instructive for me.

CH: The film is not just a story set in New York City after 9/11; it’s also centered around the relationship between father and son (Edward James Olmos and Ryan Guzman). How does the score capture Fernando’s emotional search for his father, and the emotions of his family as they hope for the father’s survival?

DER: Well, I don’t know that it does. I hope that it does, but I always approach the film emotionally—I can’t intellectualize about it—so there’s a strong family theme that we keep coming back to. There is a theme of the son’s determination, there is the theme of the journey and the friendship, and then there was the odyssey of crossing the desert [from Mexico to New York City]. These themes come back several times in the film. Also, there’s a theme about the unknown, especially when [Fernando] goes on his journey to cross the border. That is darker. It was those five simple themes that I kept coming back to and modifying or adapting.

CH: The arrangements were very simple, as well.

DER: Yeah, it’s such a naked film. I didn’t want to mess around with it that much, so I was just trying to come up with clear, concise statements that support the story and support the character.

CH: You mentioned earlier that you also performed on and co-wrote the music for some of the songs on the soundtrack. What was that experience like, and how does your background as a pop music artist/songwriter and producer help you to prepare for working on this kind of stuff?

DER: Well, I talk to a lot of young composers, and one thing that I keep coming back to is that there are no rules. We were working on the score and [Robert] had initially been talking to a record label that was going to provide a bunch of the source music, but then the price for the licensed music just became astronomical. So I said, “We don’t need it. Let’s just do it ourselves. We can do anything.”

Robert is extremely resourceful. He did the voices for several of those songs, and we just sat there and started creating. That’s what you do. Back in the band days, I was always the guy that recorded the band, so my toolkit and skill set are pretty broad in terms of that stuff. You just sit down and put up a microphone and start making noise until it works and makes sense.

CH: By voices, are we talking about Robert singing or doing vocal arrangements?

DER: Everything. Well, he sang several of the songs and wrote all the lyrics. The song “Every Tear I Cry for You” was him. I mean, he’s all over it. I contributed the music, but I didn’t write any lyrics.

CH: As both a composer and as an American, how has scoring Windows on the World impacted you?

DER: Well, it reminds me of something that I’ve always felt. I mean, I look at this immigration issue and on a very fundamental level, I think if I was the person on the other side of the wall and I had a family, I would do whatever I had to do. Again, there are no rules. The song that Robert wrote, “Inside of Us All,” was sung by David Hidalgo (of the band Los Lobos) for the opening of the film. What the song is talking about is that there’s no wall that can keep us out and that you have to do whatever you have to do to survive, and that’s what anyone would do. For a long time in this country, we’ve had the luxury of not having to fight to survive to the extent that people do across the border. It reminds me of that reality. To moralize about immigrants trying to come in is very tough to do.

CH: What projects do you have coming up?

DER: I have a friend who’s a really talented poet, artist and photographer named Jason Armstrong Beck, and a poem of his is being used by rescue.org for a public service announcement. It’s to support people who are trying to deal with being quarantined during the Covid-19 crisis. Then, a few years back, I scored a film called The Elephant in the Living Room for Michael Webber, which is a fascinating documentary about exotic animal ownership in the U.S. and how it always goes wrong for the animals. Animals always suffer. So, now he has a follow-up and I’m contributing to that. He’s been working on it for three years and he’s had a few other composers who’ve done great work, but he’s got some later scenes that I’m working on and that’s going to be really good. It’s called The Conservation Game, and he talks about how these people that are supposedly animal conservationists aren’t always what they appear to be. There’s a very dark reality to what happens to these animals that are trotted out on the morning shows, so that’s a really interesting and dark story.

—FSMO